It’s been a month since I got back from New York and I’ve finally had a chance to read through all my notes from the World Fantasy Convention. I travelled there with a grant from the Melbourne UNESCO City of Literature, and part of my grant was to bring knowledge back to writers in Melbourne. So I thought it would be useful to type up all my notes (at least the interesting ones) from some of the panels. Hopefully these contain some ideas and book recommendations for your own writing.

The Fantastic Cities of Monstrous Magnitude

As a weird fiction aficionado, there’s nothing I like better than books that evoke fantastic cities and do it well. John Clute started by discussing the definition of an edifice, that it can be both a building and a system of beliefs. This idea that there is more than meets the eye between a city and building. David Levine raised the idea that both Snoopy’s dog house and the Tardis are edifices.

As a weird fiction aficionado, there’s nothing I like better than books that evoke fantastic cities and do it well. John Clute started by discussing the definition of an edifice, that it can be both a building and a system of beliefs. This idea that there is more than meets the eye between a city and building. David Levine raised the idea that both Snoopy’s dog house and the Tardis are edifices.

John Clute said that any book on London usually has an underground and an overworld. For me, writing about cities in two spaces is always referencing in some way heaven and hell. This is used stylistically in plots as well – when studying film at university, they discussed the circular plot structure often used in detective stories; a man goes from the overworld to the underworld, just like heaven and hell, reaches the lowest point, which becomes the point where he rises back to the real world. This is most evident in David Fincher’s classic film Se7en, where they even go so far to show Morgan Freeman running down seven flights of stairs, representing the descent into hell. The other obvious example is Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere. This symbolic representation is where the city takes on a life of its own; it becomes a metaphor for something else.

There’s also a divide between fictional and non-fictional cities. It seems there are two types of writing about fantastic cities: ones where the fantasy is based in a real city or a made up one. Often urban fantasy borrows from a real location – I’m thinking of the vampire tales that have so associated New Orleans with our fanged friends. David Levine raised that it’s easier to get detail from setting in a real city as opposed to a fictional city. It’s also easier to get the reader to accept that fantasy has become part of an already existing place. He went on to discuss the idea of “mimetic fiction”, which leverages off what the reader already knows, particularly in the elements of a fantastic city. Later on, it was raised that the overworld and underworld can represent the ego and id, which is exactly what Haruki Murakami does in Hardboiled Wonderland and the End of the World.

It’s important to remember when writing about fantastic cities that they are influenced by geography and industry – they don’t exist in a vacuum and are complex systems. Linking the city to the environment it exists in separates mediocre fictional cities from exceptional ones.

John Clute raised an interesting point that “Charles Dickens has almost created a fantastic city” in his renderings of Victorian London. It was also recommended checking out the BLDG Blog (how can you not like a blog that has post titles like “Five Parises of Emptiness” and references China Miéville?).

Gemma Files pointed out that in horror, the city is either an overwhelming presence or a small town or neighborhood. Which raises the following question: Can a town or a neighborhood be considered as a city if it has the same scope for the characters? Especially if it becomes an overwhelming place of inhabitation?

Recommended books:

- A Year in the Linear City – Paul di Fillipo

- Queen of Candesce/Cities of the Air by Karl Schroeder

- Encyclopedia of Fantasy – John Clute (for edifice definition)

- Dhalgren – Samuel R. Delany

- Metropolitan – Walter Jon Williams

- Our Lady of Darkness – Fritz Leiber

- City of Stairs – Robert Jackson Bennett

- The Nikopol Trilogy/La Trilogie Nikopol – Enki Bilal (one of my particular favourites)

- Terry Pratchett’s Ankh Morpork books

- The City and the Stars – Arthur C. Clarke

- The Whispering Swarm and Mother London – Michael Moorcock

- The Arrival – Shaun Tan

- Les Cités Obscures series – Schuiten and Peeters (just look up some of the art from this BD series, it’s incredible)

- We Will All Go Down Together – Gemma Files

- The House of Shattered Wings – Aliette De Bodard

- The Sand Men – Christopher Fowler

- The Whimper of Whipped Dogs – Harlan Ellison (short story)

- In the Hills, the Cities in Books of Blood– Clive Barker

I’m really aware that this recommended reading list is mostly men, and it’s raising questions for me regarding women writing about fantastic cities (as a woman who writes about fantastic cities…). Not as a particular judgement, but more to actively seek out women writing in this area. Lauren Beukes’ body of work and KJ Bishop’s The Etched City come to mind. If you have recommendations by all means add them in the comments section below.

Fantasy and Detective Fiction: A Natural Fit?

Derek Kunsken started off by saying that “mystery works well everywhere”. Most fantasy attaches to the hardboiled, but can stretch through many genres of crime, such as cosy mysteries, procedurals and noir. Roger Turner asked “Does fantasy impose limits on what type of mysteries that can be told?” For me, this is a fascinating question – I think the answer is no, because I would say that the mystery goes as far as your imagination, but there needs to be limits on the supernatural abilities of the main characters (as with all fantasy), given reading about an investigator with omnipresent skills would be boring… or would it? Kristine Smith echoed this sentiment in saying that the detective can’t be the most powerful person in the room. Caro Soles added that the detective brings balance back to the world.

This comes into conflict with the idea that a fantasy world defies balance – nothing will go back to normal as nothing is normal. Derek Kunsken then asked whether getting back to the status quo is basically solving the crime in a fantasy novel. He also listed what makes paranormal detectives popular:

- Intelligence

- Personal integrity

- Power to render justice to kings and gods

- Touching of the mystical

- Crosses civic boundaries

- Mediates between the supernatural and not-supernatural

Interesting that most of these characteristics are what we admire about hardboiled detective fiction, especially the ability to cut across social classes (supernatural or not). Where the hardboiled detective brings down property magnates and corrupt police officials, the supernatural detective aims much higher in their targets. Whether or not a book is specified as a detective story, many fantasy books take on the characteristics of mysteries with their hero questioning the mysteries of their own past. In epic fantasy, it is often the quest for royal recognition as the hero unravels their lineage (which often turns out that they’re not just the son of the milkmaid but the son of the king and the milkmaid, and there’s been an unfortunate royal genocide in which every single possible heir before the bastard son has been killed and it’s up to the court wizard to find him out and marry him off to the nearest princess, despite his reluctant protestations that he’s in love with his feisty questing companion who he hated at first but realized that banter was her way of expressing love. Oh, and I forgot the magic sword.).

Old Weird, New Weird, or Just Plain Weird

This was my favourite panel at WFC 2015, simply because it was a room full of weird people talking about weird things.

First up, the panel started by giving their definitions of weird fiction. It seems obligatory at every con to have a panel trying to define weird fiction (I have even been on one), but in this case the panelists knew what they were talking about. Listed below are some of the reoccurring themes from weird fiction (author’s name abbreviated at the end).

- Giving a sensation of breathless and unexplainable dread. MK

- “Dark magic realism” ED

- Full of incongrouous details which build and come to a high emotional intensity which can peak or bottom out depending on an author. Stories that tap into the “strangeness of reality” – we see weird things every day. The author’s role is to pull down the curtain and show you what’s there. MM

- Defined by the person’s reaction to the story vs the style of writing GF

- Unsettling MM

- The definition should be fluid – look up the anti-definition in The Weird SN

- The reader should be left feeling discombobulated (I admire anyone who can use that word correctly in a sentence). MK

- Creepy ED

- One of the members of the audience raised that it’s about violation. I would argue that it’s about interruption – of the status quo, of the expected.

- Unexplained SN

- The word origin of weird is ‘wyrd’ – it carries an idea of destiny, things becoming due. It’s also a feminine noun. MM

- It carries a sense of inevitability, a lack of choice, drawn to an inevitable end. AM

Recommended reading:

- Bartleby the Scrivener – Herman Melville

- Lovecraft’s essay on “Supernatural Horror in Literature”

- M John Harrison

- Swan River

- Nightscript

- Experimental Film – Gemma Files

- Our lady of Darkness – Fritz Leiber

- Ceremonies – Ted Klein

- The Red Tree – Caitlin R Kiernan

- The White People – Arthur Machen

- The Weird – Edited by Jeff and Ann VanderMeer

Magic is the essential ingredient of Epic Fantasy – Except when it isn’t

This panel posed the question whether you can have epic fantasy without magic, which was neatly summed up by Kate Laity “It’s not magic that’s the problem, it’s who is using it and why.”

This panel posed the question whether you can have epic fantasy without magic, which was neatly summed up by Kate Laity “It’s not magic that’s the problem, it’s who is using it and why.”

It started with a definition of epic – it is a marker of scale, which involves nation states and large interations. Amal El-Mohtar added that the fantasy aspect is the invention of the kingdom itself. She also asked whether our view of epic was defined by battles and war, or whether this was an inherited view? Can this change? Magic can be numinous, unreliable, a technology, many different things in fantasy. (On a side note, I was totally impressed with Amal all weekend, and I picked up a copy of her book The Honey Month)

Max Gladstone asked “Does a work of fantasy exist before it is considered not-real?” Is the Illiad a work of fantasy? When did that occur? Now there’s a thought – when does a belief system graduate to fantasy? The belief systems of authors evidently infiltrate their writing, and some won’t hold sacred the supernatural elements of some religions where others would.

One of my biggest bugbears with epic fantasy is that it can be very repetitive, so I asked about it. Paul di Filippo referred to it as an “incestuous echo chamber”. Amal gave the advice to argue with and vary the source text in order to break up epic fantasy. Talk to your heroes, don’t imitate them. Max Gladstone also had good advice to invest in the skid and grunge, rather than the melodic line. “Where’s the weird static in epic fantasy?”

Recommended reading:

- Gormenghast – Mervyn Peake

- Cold Iron – Stina Leicht

- The Traitor Baru Cormorant – Seth Dickinson

- The Worm of Ouroboros – ER Eddison

- Beowulf

- Icelandic Sagas

- The Well at the World’s End – William Morris

- The Grace of Kings – Ken Liu

- The Just City – Jo Walton

- The Half-Made World – Felix Gilman

- Memoirs of a Spacewoman – Naomi Mitcheson

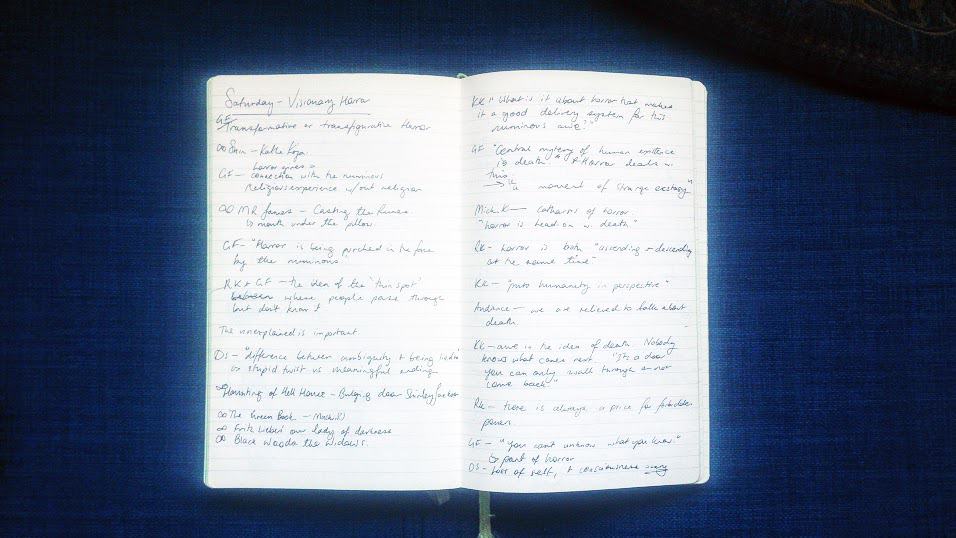

Visionary Horror

This panel was about the relationship between horror and awe, which tied in nicely with the discussions on weird fiction, where a key element is a sense of awe and wonder.

Gemma Files had a lot of good things to say, especially on the idea that horror gives a connection with the numinous, a religious experience without religion. “Horror is being punched in the face by the numinous.” Both she and Robert Knowlton discussed the idea of the ‘thin spot’ where people pass through but don’t know it. Then they get trapped in dark and strange places… a book that comes to mind which uses this technique is Graham Joyce’s Some Kind of Fairy Tale. Although it’s not horror, it is certainly very unsettling.

Derek Kunsken said that there is a “difference between ambiguity and being lied to”; a stupid twist vs a meaningful ending.

The panel descended to a discussion on death after Kathe Koja asked “What is it about horror that makes it a good delivery system for this numinous awe?” Gemma Files’ response “The central mystery of human existence is death. Horror deals with this.” It is a “movement of strange ecstasy.” Horror’s relationship to death is face-to-face. As a taboo subject, horror gives permission to speak about the unspeakable. An audience member said that we are relieved to talk about death. Kathe Koja said we are in awe in the idea of death. Nobody knows what comes next. “It’s a door you can only walk through and not come back.”

That led into the next point, by Robert Knowlton, that there is always a price for forbidden powers. Often that price is death – “you can’t unknow what you know,” said Gemma Files.

Recommended reading:

- Skin – Kathe Koja

- Casting the Runes – MR James

- Haunting of Hill House – Shirley Jackson

- Our Lady of Darkness – Fritz Lieber

Share your thoughts